Rooibos Tea - Or Redbush, Red, Bush, or Mountain Tea(!!)

How to properly brew rooibos

|

|

Okay, starting with leaf tea, as opposed to tea bags.

If you can make black tea in a pot, or with an infuser, then rooibos is a doddle.

If you want to experiment with the brewing equipment. I've used a french press very successfully. I've tried it through the espresso machine, but it's a bit weak. I know a bloke who swears by something called a "vac pot", that's usually used for coffee. Whatever shakes your tree. Another alternative some Japanese scientists reckon is best for straining all the goodness out of the tea, is to put the tea and the water in a pot or saucepan, bung it onto your stove, bring it to the boil and boil it for ten minutes. Then let it stand for as long as you can. Cold tea, they reckon, imparts more goodies than hot tea. In South Africa many people apparently drink rooibos with milk and sugar. Bronwyn doesn't drink milk in tea, and it makes Lex throw up, so we haven't tried this, but some people swear by it, not just South Africans. A number of South African cafes now use a dried out, powdered version to make what they call "red espresso". Hmmm, sounds interesting. Elsewhere, you can drink it plain, as we do, or with a slice of lemon, and if you're not yet diabetic and you have a sweet tooth which you brush regularly, you can add some sugar or honey. Or maybe some suitable sweetener. On the internet you'll see a vast and extremely tempting variety of variously flavoured versions of rooibos. If that's your baby, give them a run. Now, rooibos tea bags. Simple. Bung one (or more, if you want - it's a bit hard to put in less, although you can reduce the time the bag rests in the boiled water) in a mug, don't bother with those prissy little cups, boil the water, wait 3 minutes (or less or longer, if you want a weaker or stronger flavour), then go for your life. If you like, leave it for longer than 3 minutes, and LEAVE THE TEA BAG IN THE CUP. Rooibos just gets better and better. If you're using pot bags, perhaps 2 for a small pot, and 3-4 for a big pot. Oh, after removing the tea bag /s and disposing of it responsibly. We put ours in the compost, along with our tea leaves. Oh, yes, again, make sure you don't burn your mouth. And don't forget to try and buy rooibos in environmentally responsible tea bags. Green rooibos? Just do the same. |

Alleged health benefits

|

These tables are from a 2003 article by Laurie Erickson titled "Rooibos Tea: Research into Antioxidant and antimutagenic Properties", in Herbalgram, the American Botanical Council journal. We accessed it at http://cms.herbalgram.org

/herbalgram/issue59/article2550.html on 24 July, 2015. |

We're not here to spruik health benefits (and note, there are some claims green rooibos is not quite as beneficial with regard to some claimed uses, but we've seen no convincing evidence one way or the other). Our inclination is to doubt this stuff unless there's full scientific evidence. However, this is important to some people, so we've put it in. We suggest:

|

What is rooibos?

|

|

The Latin botanical name for the plant more commonly known as the "rooibos bush" ("rooibos" being Afrikaans for "redbush") is "aspalathus linearis". It's tea is also known variously as redbush tea, red tea, mountain tea, bush tea, Koopman’s tea, naaldtee (“needle tea”), pin tea, bossiestee (“bush tea”), and veld tea. Apparently, some black tea afficionadoes get their knickers in a knot over the use of the term "red tea" because it's also used for some black teas and Oolong tea. But who cares about them? We're sure they'll adapt, and if they don't they'll probably cark it before too long, probably during an apoplectic attack while arguing over whether the milk goes in first, or whether the water for their tea was boiled to 100 degrees or 99.5 degrees. Sorry if that's you. Actually, we guess we should be honest. We're not really sorry.

This is not the whole story, however. There are apparently some hundreds of different varieties, although they all have the same botanical name. Research has indicated that different varieties probably have different "contents" or "make-up", which may affect any benefits to be gained from its consumption. But the only reference you will get on packaging to any difference in varieties in the tea is between "wild" and "cultivated" rooibos. We touch on at least one of the reasons for this below. While we're at it, rooibos should not be mistaken for "honeybush", another legume which produces very nice tea, and which comes from around the same area. The "linearis" part of rooibos's botanical name refers to the rooibos plant's bright green, straight, needle-like leaves, although some varieties have leaves that are wider than others. It is from the leaves that the tea, perhaps more correctly called a tisane, but we won't if you won't, is made (similarly, in fact, to the honeybush plant). The leaves are harvested in late summer (January/February) by cutting about 50cm from the top of the plant. As we shall see, rooibos grows in a pretty harsh, dry area. To cope, it has a substantial tap root system that can grow to some 2-3 metres in length. Nonetheless, serious drought can cause major problems. It also has beneficial bacteria around its roots that enables it to break down nitrogen from the soil. This minimises the need for fertilising farmed rooibos. Generally speaking, wild rooibos is a fairly prostrate (blast, I keep typing "prostate") plant, while farmed rooibos bushes can grow up to 2 metres tall, although they're more commonly at around 1-1.5 metres, depending on their age. Varieties range between these two extremes. All forms of rooibos are legumes, that is, they're all related to peas and beans, and they grow pea-like yellow, or, on some varieties, yellow with a reddish-purplish base, flowers in spring. Rooibos plants are pollinated by specific solitary bee and wasp species that are adapted to carry the pollen from one flower to another. The plants grow a smooth-skinned (or is that "smooth-barked"? I guess you know what we mean) stem, which, shortly above the surface, breaks into many stems, which in turn break into small stems, upon which the leaves grow. It looks and grows rather like a broom plant. If the plant is lucky, the rooibos flowers produce a single very small, light yellow, hard-shelled seed in a pod, which is quite difficult to harvest as the seed pops out of its pod as soon as it ripens. It's not at all unknown for farmers to raid ant nests looking for "stolen" seeds, although they've developed better collection techniques in more modern times. The wild seeds need fire to germinate, with the fire breaking the hard outer shell of the seed. This can, of course, take quite some time to occur, and perhaps even longer with farmers wanting to minimise the spread of bushfires. Cultivated seeds are given a good scouring before sowing for the same reason. Apart from the division of wild and cultivated rooibos, the plants can also be divided into "re-sprouters" and "re-seeders". This refers to their ability to re-generate after bushfires. Most (but not all) wild rooibos re-sprouts from near the ground, while all cultivated varieties only re-grow from seeds. The former produce a particularly low number of seeds, while the latter are comparatively fecund. We talk about "cultivated varieties", but there is really only one. This is the nortiera variety, named after the medical practitioner and amateur botanist, Dr Peter Le Fras Nortier, who bred it around 1930 from various wild varieties he is said to have chosen for their scent and flavour. He also devised the technique of scouring the seeds to enable more rapid germination. Since that time, research on rooibos has substantially focussed on the nortiera variety. The consequence, over time, has been to change the nortiera variety in ways to improve yield, but which have also weakened its pest resistance, drought resistance, and fire resistance. This has become a major issue in recent times because of a couple of things. First, there are several pests which attack cultivated rooibos plants, but the worst is a very nasty disease called "die back", which kills massive numbers of plants every year. This disease does not appear to have an impact, or much of an impact, on wild rooibos. Second, climate change is also increasing the severity of local droughts, and this, in turn, is having a major negative impact on the nortiera plants. Third, dependence on seed re-growth after bushfires is not efficient, especially in plants that do not produce huge quantities of seed, and which take some 18 months of growth to become productive. Again, climate change is leading to an increasing number of severe bushfires, which are devastating all or parts of some properties. The answer appears to be to cross-breed nortiera with wild varieties, and indeed such research has begun, but only just. And this research is running into another problem. Bad farming habits, and the replacement of wild habitats with cultivated habitats have significantly reduced the numbers of wild rooibos plants, with at least some varieties being in danger of extinction. Indeed, the general lack of knowledge of the plant among white farmers may have already led to some extinctions. |

Where does rooibos come from?

It's probably unnecessary to say rooibos comes from South Africa. It has been tried in other countries and, indeed, other parts of South Africa, but unsuccessfully. It grows under such specific circumstances that it just won't grow anywhere else, at least not so far.

These circumstances include wet, freezing cold winters and dry, stinking hot summers, nutrient poor soil, in fact extremely nutrient poor, regular bushfires (for wild growth), occasional droughts, but not too devastating, sandy soil, and plenty of rocks. Some varieties prefer hillsides and higher locations, others prefer the flat veldt.

Without very precise conditions the plants just up and cark it, which means climate change is an exceptionally dangerous risk to rooibos cultivation, and may extinguish the species altogether.

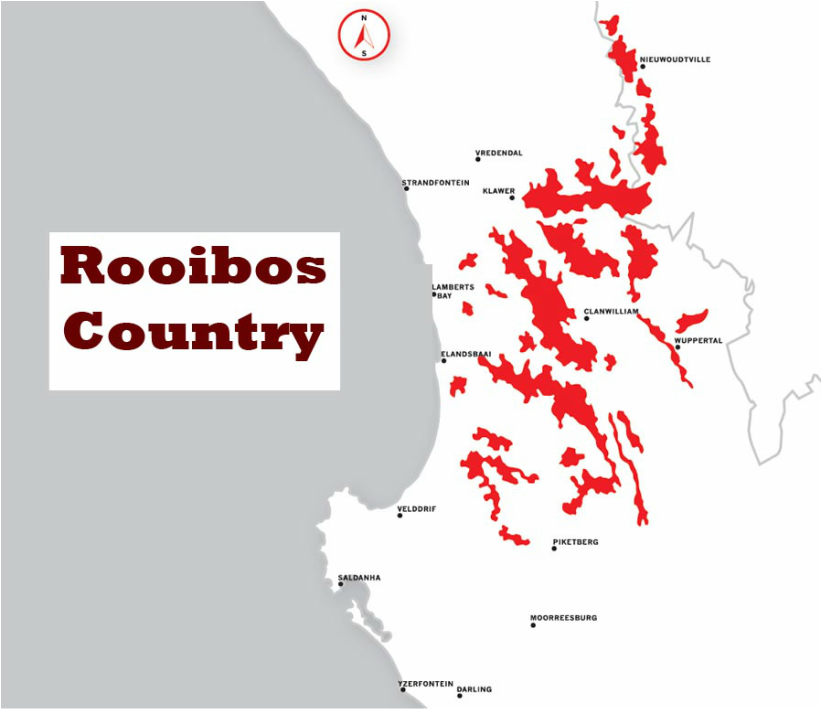

At present the only place in the entire world rooibos will grow is indicated on this map:

These circumstances include wet, freezing cold winters and dry, stinking hot summers, nutrient poor soil, in fact extremely nutrient poor, regular bushfires (for wild growth), occasional droughts, but not too devastating, sandy soil, and plenty of rocks. Some varieties prefer hillsides and higher locations, others prefer the flat veldt.

Without very precise conditions the plants just up and cark it, which means climate change is an exceptionally dangerous risk to rooibos cultivation, and may extinguish the species altogether.

At present the only place in the entire world rooibos will grow is indicated on this map:

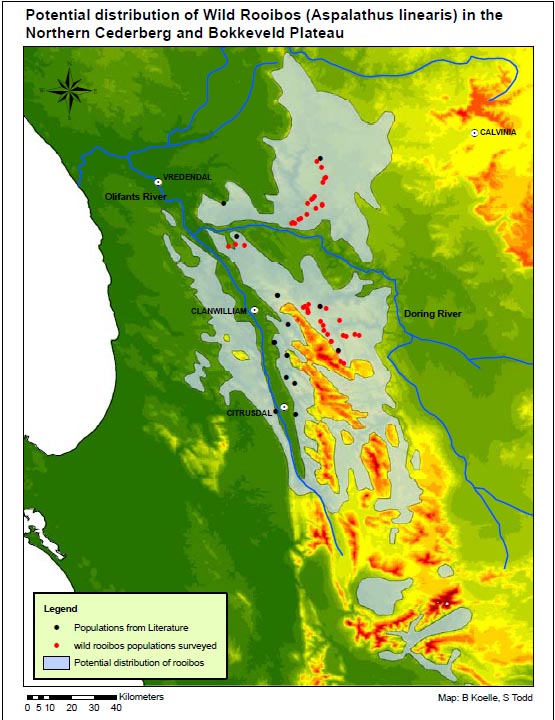

This map tells us a couple of things. First, that information on the location and growth of wild rooibos is lacking. If it weren't for the Khoisan people we would probably have even less. Secondly, that wild rooibos is effectively dying out - although that's only clear with a little knowledge of the spread it once had. Finally, cultivated rooibos has devastated the wild environment of this incredibly environmentally sensitive area, and has thus substantially reduced land available for wild rooibos, and increased the risks of climate change to wild rooibos. The dangers of this are several, but not least among them is the fact major droughts kill cultivated rooibos significantly more quickly than wild rooibos. And loss of wild rooibos reduces the chances of breeding varieties of rooibos that are good for commercial cultivation, and are capable of resisting both drought and die-back.

Some rooibos history

We don't know who first found rooibos, or who first discovered it made great tea, and how to turn it into tea. Some websites say it was Swedish naturalist Carl Thunberg in 1772. That, of course, is as nonsensical as saying it was Captain James Cook who first discovered Australia, when he wasn't even the first English person, let alone human in a continent first settled some 50-60,000 years ago. Even worse when modern humans have been living in Africa for some 200,000 years, and the San are thought to be among the first modern humans. Thunberg didn't make any such claim, he noted he realised what rooibos was good for by watching the indigenous people.

In the 19 noughties, a bloke called Ginsberg began to commercialise rooibos. He battled along with wild and cultivated rooibos until his mate Nortier perfected plant and process. But it was still pretty small-scale. During WW2 black tea was extremely hard to come by, so rooibos started to replace it. After WW2, things really started to grow. Initially it was small farmers who got stuck in, but as the market continued to grow, especially with health food kicks and the like over the last 40 or so years, the big guys have moved in. The business is extremely large now, and is primarily plantation-based.

But of course, when the farmers and plantations moved in, whites one and all, they occupied land that actually belonged to others, the indigenous people, mostly known as Khoisan. The people whose ancestors discovered the value and uses of rooibos were pushed to the very outskirts of rooibos country. The whites then ripped up the habitat of the wild rooibos and replaced it with disease and drought prone cultivated rooibos. Fortunately, with assistance from various organisations, a number of Khoisan people have returned to the rooibos industry in roles different from being employees on white farms and plantations. Various co-ops and other techniques have been used to develop strong businesses utilising various mixtures of wild and farmed rooibos.

In the 19 noughties, a bloke called Ginsberg began to commercialise rooibos. He battled along with wild and cultivated rooibos until his mate Nortier perfected plant and process. But it was still pretty small-scale. During WW2 black tea was extremely hard to come by, so rooibos started to replace it. After WW2, things really started to grow. Initially it was small farmers who got stuck in, but as the market continued to grow, especially with health food kicks and the like over the last 40 or so years, the big guys have moved in. The business is extremely large now, and is primarily plantation-based.

But of course, when the farmers and plantations moved in, whites one and all, they occupied land that actually belonged to others, the indigenous people, mostly known as Khoisan. The people whose ancestors discovered the value and uses of rooibos were pushed to the very outskirts of rooibos country. The whites then ripped up the habitat of the wild rooibos and replaced it with disease and drought prone cultivated rooibos. Fortunately, with assistance from various organisations, a number of Khoisan people have returned to the rooibos industry in roles different from being employees on white farms and plantations. Various co-ops and other techniques have been used to develop strong businesses utilising various mixtures of wild and farmed rooibos.

How is rooibos made?

|

The better quality rooibos usually comes from areas with that are higher up, have a lower rainfall, and as a result generally have a lower yield. That's right, folks, rooibos has various qualities. That's something that doesn't tend to be entered on the packaging.

Practices vary somewhat, but typically a rooibos field is harvested annually for about 4-7 years. Then a rotation crop, usually oats, is planted for 1-3 years to provide fields with a "recovery" period where nutrients are returned to the land. While cultivated rooibos can be harvested annually, wild rooibos can mostly be harvested only every 2 or so years because of its slower regrowth rate, although some varieties can be harvested annually. Seed is collected from mature plants (about 18 months and older) and, occasionally, very occasionally these days, from ants nests. It's germinated around the end of January, and tended in a nursery area for around 4 months. As winter starts to cool, the seedlings are planted, either by hand or by machine. Around January, February, March the rooibos is harvested by cutting off the tops of the plants. Some farms and plantations cut off 40-50cm, and some properties cut down to about that far from the ground. Wild rooibos generally isn't cut as much as its regrowth is so slow. Having said that, some can be cut more than others. Harvesting is mostly done by hand, using sickles, although there is some use of harvesting machines. This is probably an indication of the cheapness of labour. But of course if wages and conditions are improved, the plantations would just get rid of their workers and use machines. The cut branches are bundled together and carried to what is called a "tea court". Here they're fed into cutting machines, which both cut the leaves and branches into 1mm to 5mm lengths, depending on the customers' requirements, and bruises the cuttings. The higher the leaf content and the smaller the cut, the higher the quality of the tea. By this time the rooibos is wet. It is then placed in a long, low heap across the tea court to undergo a process called “sweating”. This stage has to be carefully managed and controlled. What they're aiming for is what is called an "enzymatic oxidation", which is to occur during a fermentation stage which results in the rooibos changing from green to the more recognisable red/amber color with the flavor and aroma we know from our tea. The rooibos is now sun dried. Then it's sifted and pasteurised to get rid of nasties, like rat droppings and germs. The whole process from cutting to drying takes about 24 hours. It is now ready for packaging and retail. For those of you who drink green rooibos, it undergoes much then same process, except it avoids the fermentation stage, and goes straight from cutting to drying. |

Location

|

|