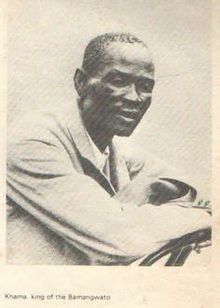

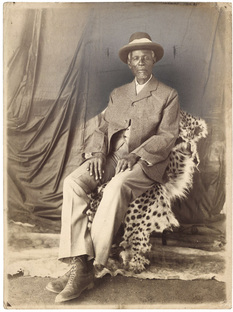

Khama III

Khama III (ca 1837-1923)

By the latter half of the 19th century, what we now know as Botswana was split into eight pretty much self-administering territories, made up, of course, of the eight merafe (each specific tribal group, or "nation", under the command of a kgosi, or "king"), as well as several white settler areas. The remainder, such as it was, was classified as Crown land, in essence owned by the British.

Khama - Livingstone Interferes

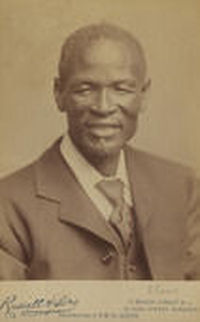

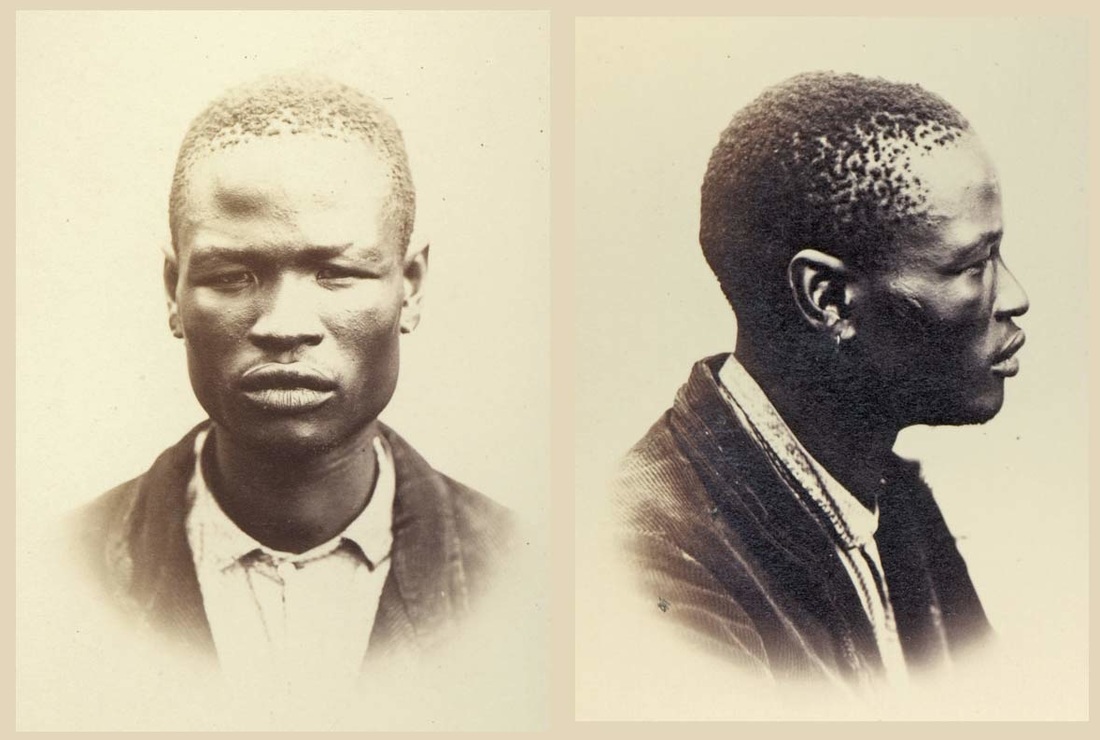

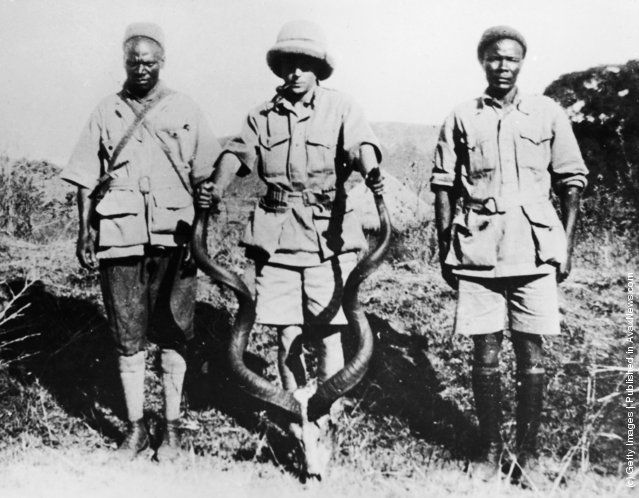

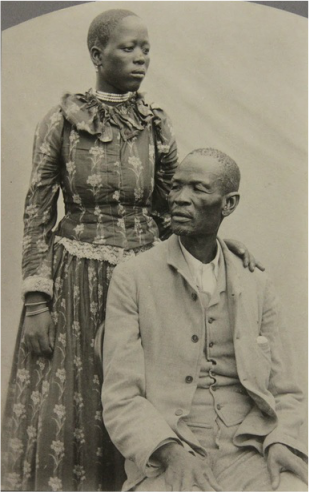

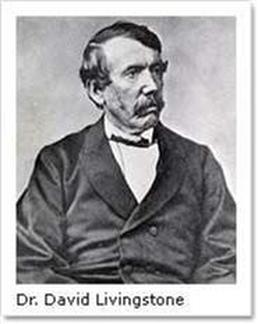

Just for the moment, we will follow a bloke called Khama III. Well, at least, as far as his death in 1923. Born around 1837, he led what one could call a hell of a life. And what a film it would make. The missionary David Livingstone (the bloke on the left there) did at least two things that had a major impact on Khama. First, when Khama was in his twenties, he was converted to christianity and baptised by Livingstone.

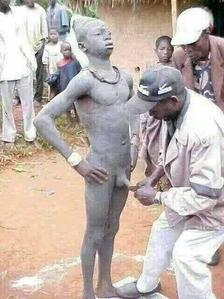

Khama & Bogwera

Prior to this, Khama had already undertaken the merafe’s initiation into manhood (called a "bogwera") in company with his mephato ("age regiment"). In the past, bogwera involved extensive tests of strength and survival, including circumcision, and some sources say concluded with the killing of one of the mephato as a process of purification and strengthening. We're unable to find out whether the killing of one of Khama’s mephato took place, or, indeed, whether such killings ever took place.

By the latter half of the 19th century, what we now know as Botswana was split into eight pretty much self-administering territories, made up, of course, of the eight merafe (each specific tribal group, or "nation", under the command of a kgosi, or "king"), as well as several white settler areas. The remainder, such as it was, was classified as Crown land, in essence owned by the British.

Khama - Livingstone Interferes

Just for the moment, we will follow a bloke called Khama III. Well, at least, as far as his death in 1923. Born around 1837, he led what one could call a hell of a life. And what a film it would make. The missionary David Livingstone (the bloke on the left there) did at least two things that had a major impact on Khama. First, when Khama was in his twenties, he was converted to christianity and baptised by Livingstone.

Khama & Bogwera

Prior to this, Khama had already undertaken the merafe’s initiation into manhood (called a "bogwera") in company with his mephato ("age regiment"). In the past, bogwera involved extensive tests of strength and survival, including circumcision, and some sources say concluded with the killing of one of the mephato as a process of purification and strengthening. We're unable to find out whether the killing of one of Khama’s mephato took place, or, indeed, whether such killings ever took place.

|

|

Khama becomes christian

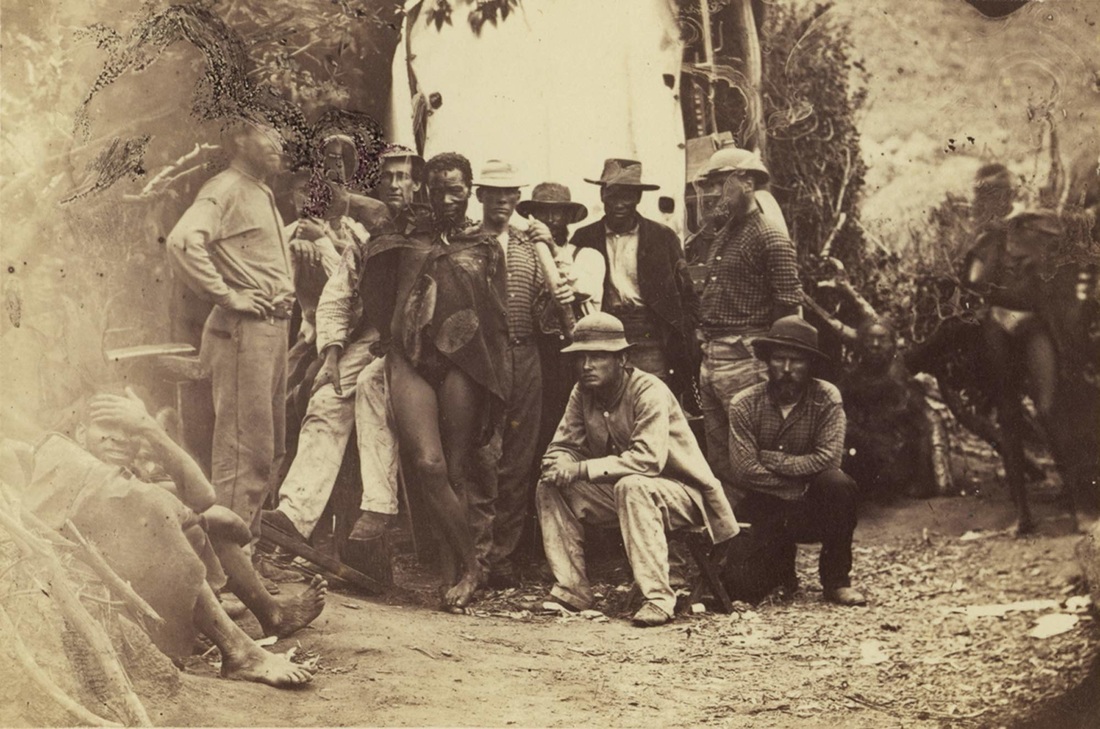

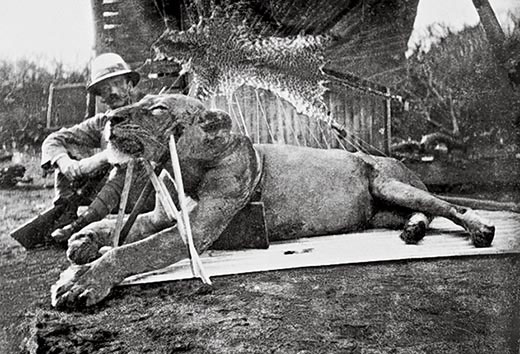

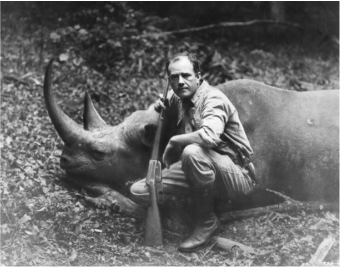

One would possibly have thought that after all this Khama would have a powerful commitment to the traditional beliefs. But apparently not. Perhaps the circumcision was such a bugger he just hated tradition - certainly, it was, with alcohol and slavery, one of the things he banned as soon as he was able. Whatever, it's unknown just what his motivation for conversion was. Of course, it may be that Khama found God, as the missionaries believed. Or it may have been much more complex, and possibly more power-orientated than that, bearing in mind that he led his immediate followers, and others of his merafe into christianity, establishing a counter bloc to his father, the kgosi, and, ultimately, his estranged brother. At first, Khama's father, Sekgoma I, accepted what his son had done, although it was a begrudging acceptance, and he did not convert himself, nor did his immediate followers. Khama, Livingstone & Trophy Hunting Now we come to Livingstone’s second major impact on Khama. In 1849 Livingstone’s exploration work opened up the Kalahari to wealthy Europeans, Americans, and white South Africans, causing the start of a large hunting and hunting products trading boom lasting into the late 1870s. A loose coalition of Sekgoma and Khama’s BaNgwato, and the Bakwena, BaNgwaketse, and Batawana merafe pretty much controlled the hunting business. This coalition organised hunts using guns, mounted men, and Bushmen, who were also often forced to pay tribute in the form of various hunting products. Khama was a leader of this work for the BaNgwato, and through it he restructured his morafe’s economy, and helped spread its control over further lands and their people. |

|

Khama & his old man get to rumble

Eventually, however, Sekgoma and Khama entered into open conflict. The morafe was based in Shoshong, near modern Mahalapye. What followed is the stuff of novels, but this was real life, and with even more extraordinary characteristics than we've put down here:

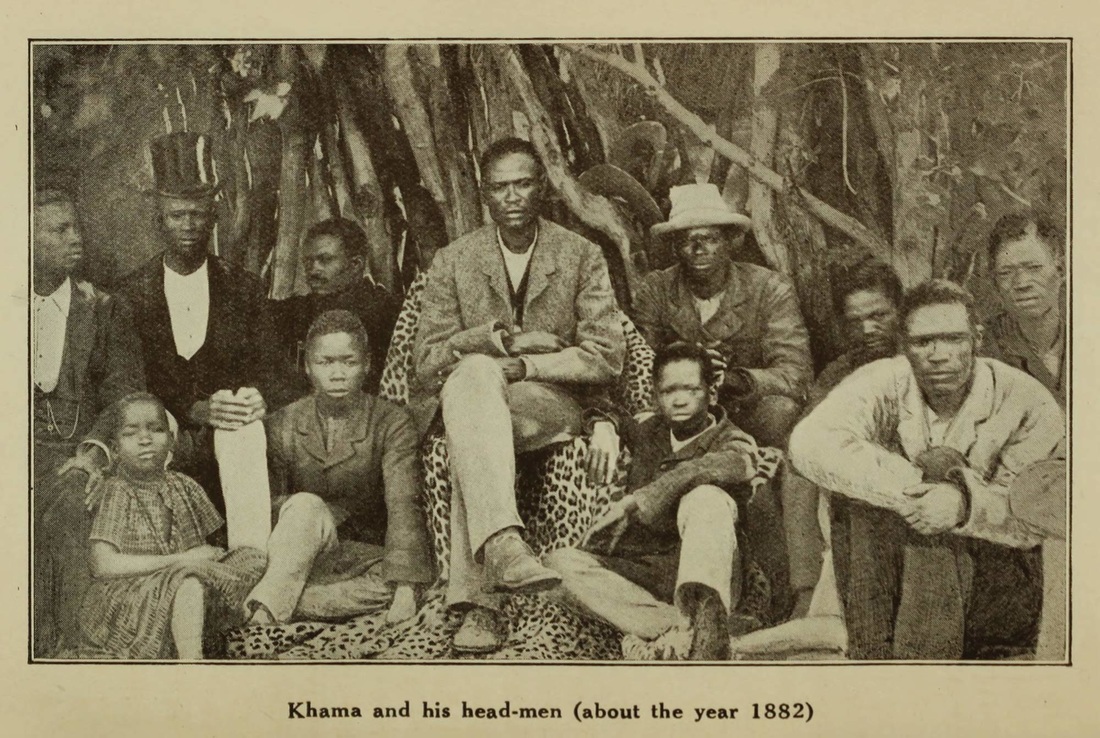

Good grief. What a movie this would make? Or even better, considering the range of events and time, a major TV series. Wow. But nearly as incredible is the story of his grandson. Don’t worry, we’ll get to that. Eventually. Shoshong grew rapidly in population, power, and wealth. At its height its population was some 30,000, at a time South Africa's Cape Town's population was around 33,000. Khama could support a military force of around 3,000 men, and his farmers grew great quantities of corn and developed great herds of cattle, as well as sheep and goats. Of course, this meant Khama had a surplus he could trade. As more and more Europeans made their way to and through Shoshong, Khama made sure he controlled all wagons, and that they came through Shoshong and traded with his people. This quickly enabled him to manage and develop other forms of trade. For example, in 1878, 75 tons of ivory from 12,000 elephants was exported via Shoshong and in 1879 Shoshong's total export of ivory was worth £30,000. There are umpteen ways of calculating the worth of this amount at the time of writing, 2015. Depending on the purpose of the calculator, they range from £2 million to £40 million. Under the circumstances of this bit of writing we think the upper amount is probably closer to the mark. Of course, nowhere near all of this was left in Shoshong, but Khama made sure he and his people got their share. As noted already, Khama refused to get involved in two sources of trade and wealth, alcohol and slavery. In the early days of trade, mostly pre-Khama, the Europeans had bought ivory, feathers and animal skins in exchange for beads and brass wire. But Khama was much more canny than that. He and his people started to insist on clothing, guns, ammunition and ploughs. And it was the latter that grew greatly in demand. As we know, Khama died in 1923. His father must have used the wrong magic spell when he tried to kill him. Or perhaps he should have said the spell backwards. Anyway, his eldest son, Sekgoma II, took over after him, but only lived for about a year further. Sekgoma II left a son, Seretse, who was only four. While Seretse’s story is as interesting as Khama III’s, it is fortunately not as full of violent adventure. Upon Sekgoma II’s death, it was agreed that his younger brother, by a later wife of Khama’s, Tshekedi, would take over as regent until Seretse was ready and able to take over. |

Location

|

|